Insured vs. Self-Insured for State Insurance Programs

THE RHA REVIEW

September 2017

By Stephen S. Collins

This article is based on data I gathered for an analysis of the Commonwealth of Kentucky’s insurance program several years ago while serving as an executive advisor for the Kentucky Department of Insurance. The main reasons I recommended the analysis to the insurance commissioner were my prior experience as claims manager for Ashland, Inc., and my familiarity with trends in the self-insurance/SRIs of many Fortune 500 companies. It is an analysis I would recommend for all state insurance programs on a periodic basis.

My review included two operations that fall within the Kentucky State Risk Division’s coverage provided by the State Fire and Tornado Insurance Fund (SF&T) and the insurance program covering state automobiles.

Before I discuss SF&T and the state’s auto coverage, it is important to restate the basic definition of insurance and understand how it applies to the state’s unique ability to assume risk and pay losses. According to the late Dr. James L. Athearn, former professor of insurance at the University of South Carolina:

(Insurance) is a social device which combines the risks of individuals into a group, using funds contributed by members of the group to pay for losses. The funds may be accumulated in advance or through assessments following a loss.

In considering the insurance needs of the state, the ability to accumulate funds over a period of time, before or after a loss, is a major consideration, as is the fact that the individuals who form the insured group and own the assets at risk are the citizens and taxpayers of the state.

Commonwealth of Kentucky — State Fire and Tornado Insurance Fund

The State Fire and Tornado Insurance Fund (SF&T) was created by an act of the 1936 Kentucky General Assembly. The act has been modified over the last 80 years, as set out in KRS Chapter 56. SF&T was formed to provide fire and windstorm insurance coverage for state properties and was funded with an initial $100,000 appropriation. In 1936 the conception and creation of SF&T were innovative, cutting-edge thinking. The evolution of SF&T to its present form has failed to maintain the foresight shown by the 1936 General Assembly. The value of state property has grown at a significant rate, whereas the level of insurance provided by SF&T has not increased at a rate proportional to that in the original act. The history of SF&T from 1936 to 1995 is set out in a July 11, 1995 report prepared by B. R. Partin, director of the State Risk and Insurance Services Division. I have relied on this report for historical information.

The SF&T policy is a manuscript policy, although much of the language follows standard ISO policy form language. The Fire and Extended Coverage section of the policy provides all-risks coverage on real and personal property, as required by KRS Chapter 56. The policy, for an additional premium, has available inland marine coverage, telephone system coverage, electronic data-processing coverage, and business income and extra expense coverage. The policy has the standard industry exclusions, including war, military acts and terrorism.

In the study policy year (July 1, 2007 – July 1, 2008), $700,000,000 of excess insurance overlies the $500,000 provided by the SF&T. This coverage is provided by National Union Fire Insurance Company ($500,000,000) and Travelers ($200,000,000). In prior coverage years, multiple coverage layers insured by various companies provided the coverage excess of the SF&T policy. National Union’s $500,000,000 of excess coverage has several sub limits. The most significant of these is the $100,000,000 policy year aggregate limit for floods and the $100,000,000 policy year aggregate limit for earthquakes. The Traveler’s policy has various “ground up” sub limits that in effect exclude these coverages, subject to sub limits in the National Union policy.

In reviewing SF&T and the state’s property insurance program, the following questions needed to be answered:

(1) Should the state become fully self-insured or have an increased self-insured retention in its property insurance program?

To answer question (1) requires a review of the state’s property-loss history to determine the amount of losses paid by excess insurance and the premiums paid to excess insurers.

The World Trade Center and Pentagon terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 changed market conditions. The cost to purchase primary and excess property insurance has increased significantly. To use period market costs in the analysis, we believed that the data used should be post 9/11.

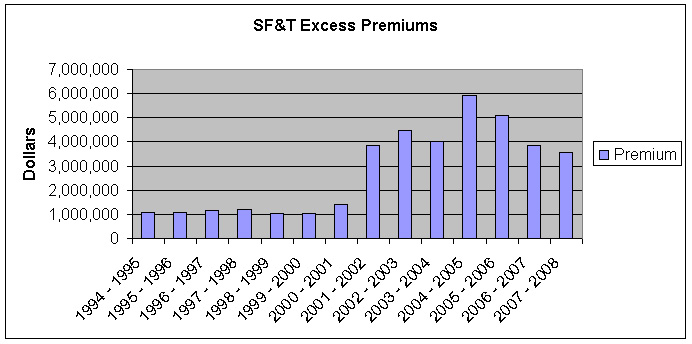

The graph below illustrates the post 9/11 market increase:

The chart below shows the actual post 9/11 excess losses and excess premiums paid:

Excess Losses Paid vs. Excess Premiums Paid – Property Coverage

For the policy periods 12/31/01 through 07/01/08, the average annual excess losses paid were $354,723, and the average annual excess premium paid was $4,149,923. If the state had been self-insured for this time period, the average annual savings, less a small percentage for claims-adjustment costs, would have been $3,795,200 per year, or a total savings of $24,668,800 for the period.

Although there is significant justification for using only the post 9/11/2001 premiums and loss numbers, the post 9/11 analysis omits the Commonwealth’s largest historical loss.

On May 15, 2001, a fire severely damaged the University of Kentucky Administration Building, leading to a loss of $9,796,714. A payment of $7,000,000 was recovered from the insurance company of the contractor, whose employee started the fire. After legal expenses, the net recovery was $5,826,000. The net loss paid by the state’s excess carriers was $3,970,714.

Using the 10 years between July 1998 and July 2008 (which includes the 2001 UK fire loss), the average annual excess losses paid were $633,426. The average annual excess premiums paid were $3,415,846. If the state had been self-insured for this 10-year period, the average annual savings would have been $2,782,420, less claims handling expense. Thus the savings for the 10-year period would have been $27,824,203.

Given the excess insurance premiums paid and the state’s loss history, the answer to question (1) is clear: the state should become fully self-insured for property losses.

(2) How would a new State Property Insurance Fund operate?

A new State Property Insurance Fund (SPIF) would operate almost identically to the current State Fire and Tornado Insurance Fund (SF&T). It would require KRS Chapter 56 to be rewritten using today’s best practices and strict insurance and accounting standards for the statutory operation of the SPIF.

The fund would collect insurance premiums from state agencies based on the coverage required and the value of the property insured. Premiums paid, less administrative expenses, would go into SPIF to pay current and future losses. It should be the initial goal of SPIF, based on the state’s historical loss ratio, to provide state agencies with property insurance at a rate of 30 percent below the market rate. When the assets of the new fund increased to an actuarially determined amount sufficient to pay losses, premiums would be further reduced for state agencies, based on each agency’s loss experience and compliance with required loss-control measures.

SPIF would establish policy limits based on the state’s Maximum Foreseeable Loss. Maximum Foreseeable Loss is defined as: the largest loss expected with no credit given for protective systems such as sprinklers or internal emergency response. Insurance consultant Marsh & McLennan Companies (Marsh) conducted a Maximum Foreseeable Loss Study for the Commonwealth and reported its findings in a report on August 9, 2007. The purpose of the report is best set out in Marsh’s own words:

This study has been conducted to identify loss scenarios which, while unlikely to occur, would result in the highest financial impact to the Commonwealth and its insurers.

According to the Marsh study, a significant fire at the University of Kentucky’s W.T. Young Library could result in the Commonwealth’s Maximum Foreseeable Loss. Again, to quote the Marsh report:

A fire starting on the first floor of this building in the kitchen area with all protective systems out of service, including sprinklers and fire shutters, would be expected to involve all areas and all levels due to the open construction features and vertical openings. There are not sufficient horizontal breaks in the continuity of combustibles to consider the presence of a natural fire stop. It is expected that the building would suffer total constructive loss of 100% property damage or essentially such extensive damage such that meaningful repair is not possible.

The replacement cost reported value of the W.T. Young Library and its contents (at the time of the study) was $135,524,585. This amount represented the Commonwealth’s Maximum Foreseeable Loss and would be used to determine the amount of coverage provided by SF&T + Excess Insurance or a new SPIF.

We need to consider the fact that a loss caused by an earthquake is not considered the Maximum Foreseeable Loss. Clearly a significant earthquake centered near any large cluster of state buildings, such as the UK Medical Center and UK campus (or more likely, because of the New Madrid Fault, Murray State University), would result in a loss of catastrophic proportions. Under the state’s 2007 excess coverage, the insurance payable for an earthquake loss was $100,000,000. The Maximum Foreseeable Loss resulting from an earthquake and the ways to best structure earthquake coverage require further study.

State Automobile Insurance Coverage

For the study/analysis period, state automobile insurance coverage was under a Blanket Auto Policy provided by Travelers Insurance Company (Travelers). The policy period was July 1, 2007, 12:01 a.m. through July 1, 2008, 12:01 a.m. The primary liability coverage was $350,000 (Combined Single Limit), with additional excess coverage of $650,000 (Combined Single Limit), which was available for those agencies that regularly transport non-state employees, such as the Department of Corrections transporting prisoners or the Health and Family Services Cabinet transporting children. Comprehensive and Collision Coverage applied to select vehicles as identified in the state’s schedule of vehicles.

In reviewing the state’s automobile insurance programs, we need to consider the same questions we asked about SF&T:

(1) Should the state self-insure a Blanket Auto Policy (BAP)?

When I began the auto coverage review, I will admit to being somewhat surprised to find that the state had first dollar insurance coverage on its fleet of vehicles. The economic sense of an entity, such as the Commonwealth of Kentucky, being either fully self-insured or having a large self-insured retention, has long been a proven reality. The majority of Fortune 500 companies have either self-insured retentions or “front” their primary insurance coverage. In an article written for The Metropolitan, Corporate Counsel John P. Henry wrote:

Fortune 500 corporations have increasingly opted to self-insure, with retentions of at least $3 to $5 million per occurrence, and often $25 million or more. They have looked to insurance companies only for coverage of catastrophic events. The insurance industry is not seen as offering cost-effective first-dollar or low-retention coverage.

The state’s five-year auto coverage, for the study period, loss/premium paid history is in the table below:

Losses Incurred vs. Premiums Paid – State Auto Coverage

* Total Incurred = claims paid + outstanding reserves on open claims.

For the five-year period, from 07/01/02 – 07/01/07, the average annual auto premium paid by the Commonwealth was $3,133,601. The average annual claims cost was $1,737,682. Less an estimated annual claims handling cost of $155,360, had the state been self-insured for the five-year period, the average annual savings would have been $1,240,559. The total savings for the five-year period would have been $6,202,795.

Based on losses compared to premiums paid, it is clear that the state should consolidate and self-insure its auto coverage.

(2) How would a state self-insured auto program operate?

Several available options achieve the same self-insured effect; we will briefly discuss three:

The state could use a “Fronting Program.” In a fronting program, an established insurance company provides a Blanket Auto Policy (BAP). The BAP has a deductible equal to the coverage limit or is reinsured by the insured’s fully owned captive. Claims are handled by the fronting insurance company as if the coverage was first dollar and the claims handling costs are paid by the insured. A significantly reduced premium is paid to the insurance company for the policy. The insured has the ability to retain oversight of claims handling and payments.

The state could go “bare.” The state would not have automobile insurance or a State Self-Insurance Fund. Claims against the state would be handled by the Board of Claims with a statutory cap.

The third option is a State Auto Insurance Fund (SAIF). The formation and operation of SAIF could be included in the statutory language under KRS Chapter 56. SAIF would operate very similarly to the State Property Insurance Fund, with a statutory policy limit.

In each example above, the legislature has the ability under “sovereign immunity” to limit the state’s liability. In a paper on Kentucky Governmental Liability prepared by the

Honorable John Burkholder for the Defense Research Institute, he summarized:

The Supreme Court of Kentucky redefined the source of Kentucky’s “sovereign immunity” as inherently arising from the common law of England. Reyes v. Hardin County, 55 S.W. 3rd 337, 338 (Ky. 2001) …. The General Assembly alone can specifically waive sovereign immunity as it did in the Board of Claims Act. When the General Assembly authorizes the purchase of insurance or self-insurance, it does not expressly waive sovereign immunity.

Conclusion

The reason for a state insurance program to exist is to protect, by the most cost-effective means possible, the citizens and taxpayers of the state from the financial impact of the loss of state assets. In carrying out their responsibilities, state insurance programs need to be mindful of the simple definition of insurance and the unique abilities of the insured group to withstand and fund losses.

The dollars that would have been retained by the Commonwealth of Kentucky in the Losses Paid vs. Premiums Paid comparisons are impressive. To retain those dollars, the state must assume the risk of loss and must be prepared to pay future losses. In establishing new state self-insured funds for property and auto insurance coverage, premiums from state agencies would still need to be collected. The new insurance funds would not necessarily require an initial allocation from the General Assembly, with the understanding that losses could exceed funds available in the short term. A cost-effective mechanism would need to be in place to pay unfunded losses. Reimbursement for unfunded losses would be paid from the insurance funds as premiums were collected. When the insurance funds accumulated to an actuarially-determined level sufficient to pay foreseeable future losses, based on loss-experience and loss-control compliance, premiums to state agencies would be reduced.

A significant number of states now have self-insurance programs for property and automobile insurance coverage. Most Fortune 500 companies self-insure or have very large loss retentions, buying insurance only for losses in excess of $5 to $25 million. The current Kentucky General Assembly has the opportunity to be as bold and creative in its thinking as were the legislators in the 1936 General Assembly. Kentucky should determine, based on outcome and performance, the “best practices” of the various states’ self-insurance programs. Using the best information available, the Kentucky Legislature needs to rewrite KRS Chapter 56, establishing a new property and auto self-insurance fund (or funds), wherein Kentucky fully self-insures losses or where there exists a very large loss exposure, buying excess insurance (if reasonably priced/available in the market) only for large catastrophic losses.

The assets of the Commonwealth of Kentucky are owned by the taxpayers and citizens of this state. This large diverse group has the ability to assume the risk of loss of state assets and to financially recover after a significant loss. Given that the state’s risk is already shared by so many, it is not cost-effective to pay tax dollars to private insurers.