Welcome to Alice's World

Insurance Policy Limits

THE RHA REVIEW

Volume 7, No. 4, Third Quarter 2001

By Robert N. Hughes, CPCU, ARM

"I don't understand you," said Alice. "It's dreadfully confusing!"

"That's the effect of living backwards," the Queen said kindly: "it always makes one a little giddy at first."

"Living backwards!" Alice repeated in great astonishment. "I never heard of such a thing!"

". . . but there's one great advantage in it, that one's memory works both ways."

"I'm sure mine only works one way," Alice remarked. "I can't remember things before they happen."

"It's a poor sort of memory that only works backwards," the Queen remarked.

Lewis Carroll, Through the Looking Glass, Longmeadow Press, 1982.

Okay, gang, listen up! Here's the scenario. It's renewal time and you are trying to figure out how much liability insurance you should purchase for your company. Got it? Okay, now let's have a show of hands from everyone who believes that two very important elements that must be considered when making this decision are (1) what your liability limits on past expired policies were, and (2) what limits you plan to purchase in future years. Well, imagine that. Not a single hand showing.

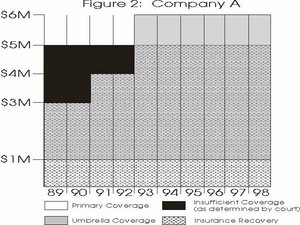

All right, let's try another one. Let's say that your company (Company A) and your competitor across the street (Company B) made an identical product from 1989 to 1999 and, lo and behold, both products developed exactly the same defect, causing liability claims in the amount of $50,000,000 against each company. Further, let's assume that Company A purchased $1,000,000 in primary coverage each year for 10 years. In addition, it bought an additional $2,000,000 of umbrella coverage in 1989 and 1990 (a total of $3,000,000), an additional $1,000,000 in 1991 and 1992 (a total of $4,000,000), and an additional $2,000,000 in 1993 (a total of $6,000,000) for the remaining six years. The total coverage for the 10-year span equaled $50,000,000.

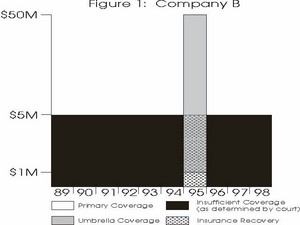

At the same time, Company B across the street purchased coverage only in 1995. Its coverage was a $1,000,000 primary CGL with an umbrella of $49,000,000 on top of that.

Finally, let's assume that while the claims were all made in the year 2000, the damage that resulted in those claims happened between 1989 and 1999, although it is impossible to determine in which specific year the damage occurred. Now let's have another show of hands. How many of you believe each company should have $50,000,000 in coverage applicable to these claims? Remember now, these policies promise to pay "all sums" that the insured becomes legally obligated to pay as a result of bodily injury or property damage during the policy period. About half of you, I see. I presume that means the rest of you either think there will be some disparity in the total amount paid on behalf of the insured or you just don't know. If so, don't feel bad. Courts all over the United States are in the same boat.

Let's change the hypothetical a little bit just to try to demonstrate to you what is really happening. Suppose that one fine day some EPA representatives come tap, tap, tapping, gently rapping at both your chamber doors. They say something like this: "We've discovered this entire area is covered with toxic substances. It's getting into the groundwater, and you may be responsible. As such, under the Comprehensive Environmental Response Compensation and Liabilities Act (CERCLA), you are jointly and severally liable for cleaning up all the damage, regardless of when it happened. Fix it or we will do so and bill you for it." Your engineers tell you it is going to cost $50,000,000 to clean up the site.

Now think about the previous question and let me see the hands of those who believe each company has a total of $50,000,000 in coverage applicable to the damage (assuming no exclusions apply). Aha, almost all of you. Unfortunately, the insurance companies disagree. Here's the story.

Policyholders say, "Look, my policies all say they will pay 'all sums' and all that has to happen in order for those policies to be 'triggered' is that at least part of the total damage must occur during the policy period. I calculate my exposures and buy my policies on a year-by-year basis. Therefore, since all the policies are triggered, I should be able to pick any year during the span of damage and call upon those insurers to pay all or any part of the damages." This is called "vertical allocation" and is sometimes referred to as the "pick and choose" or "joint and several" theory.

Insurance companies say, "No, that's not right. First, you have to exhaust all the limits of all the primary coverage you bought over the span of the damage. This means that nonsettling primary carriers give excess carriers an excuse for not paying. Once the primary has paid, however, each excess policy contributes on a pro-rata basis until each policy is exhausted." Think of a coverage chart that spans the 10 years as a glass container into which you pour water. The water seeks its own level and rises all across the chronological span of coverage. As coverage years "fill up," more water is pushed to the remaining columns. This is known as "horizontal" exhaustion and is sometimes referred to as the "beaker" theory or the "bathtub" theory.

As long as the policyholder gets the benefit of all the coverage it purchased, it doesn't particularly make any difference. Here's the rub, however. Some courts have held that in years in which the policyholder purchased "insufficient" coverage (as determined by a special master appointed by the court), then the policyholder has to contribute to the loss in the same degree as that "insufficiency" bears to the total damages. So, in our example, let's suppose that the special master rules that both companies could have purchased $10,000,000 in coverage for each of the 10 years in question. Horizontal allocation with a penalty for under-insurance would then mandate that Company B receive only 10 percent of its insurance proceeds, or $5,000,000. It is held responsible for the entire $5,000,000 allocated cost in all years except 1995 because it is treated as the "insurer" of up to $10,000,000 in each of those nine years (see Figure 1). Company A, by contrast, would have to participate in the layers excess of $3,000,000 and $4,000,000 in 1989-1992 and would receive only $44,000,000 in spite of the fact that it had purchased $50,000,000 in coverage, all of which was triggered (see Figure 2).

Had risk managers known of this potential in 1993, how in the world would they have decided what limits to purchase? They would have had to compare all the coverage they had purchased in the past with what might have been available (arguable at best) and then plan their future purchases as well. Suppose also that the maximum limits were calculated on the basis of "maximum probable loss." If future events proved that amount to be insufficient, and if some court determined that higher limits were available, then the insured would suffer not only the penalty of insufficient limits but would also be required to be a co-insurer in the lower layers.

But as if that were not bad enough, another element has entered the picture. That element is insolvent insurers, of which there are many. Now some courts are saying that having an insolvent insurer in any of these layers of coverage places policyholders in the same position as if they had purchased no insurance at all for that layer. Therefore, they become subject to the aforementioned under-insurance penalty in horizontal allocation. So, not only must policyholders be prescient and therefore able to perceive what limits they will purchase in the future, they must also be omniscient and able to know what limits of coverage were available in the past and what will be available in the future. Surely the only way to do that is with the help of Alice's famous looking glass.

In summary, then, under the "horizontal" theory of allocation, you must first settle with all of the primary carriers that issued policies during the span of the damages, and then you must contribute with the excess carriers in any years in which you are deemed by some judge not to have purchased adequate coverage. All this in spite of the fact that you have paid a premium for every policy and that every policy, under its specific terms, is triggered and responsible for paying "all sums" which you are legally obligated to pay as a result of the long-term occurrence. Make sense? Hardly.